Tariffs hurt – because we let them hurt

Not reacting to tariffs is not the same thing as not responding to them

“Liberation Day” – 2nd April. A day that will probably go down as one of the most crazy acts of self-harm is modern economic history. Trump has long mooted a change to US economic policy, moving the country back towards a protectionist approach. This has been predicated on the idea that countries with which the US has a trade deficit (EU, China, Canada, Mexico) are somehow ‘stealing’ from the US.

Trump has also looked at tariffs as a means of delivering new finance for the US government. On the election campaign trail, he talked about moving from an ‘Internal Revenue Service’ to an ‘External Revenue Service’. Tariffs are seen by Trump as a means of financing potential cuts to income taxes and creating jobs in the US – particularly manufacturing jobs.

There appears to be a pattern with ‘libertarian’ right-wing governments around the world. Liz Truss thought that she could take on the debt market and win. She could not. Xavier Milei thought that slashing government would make him popular and would lift people's standard of living. Now more than 60% of Argentinians think their quality of life has fallen on his watch. There is a strong sense of hubris about what is possible and what can be delivered.

Tariff Decision

Trump announced that tariffs would be applied to all goods imports (not services). There would be a global 10% tariff minimum. The 10% universal tariff will go into effect on 5 April. Additional reciprocal tariff levels would rise from that 10% minimum depending upon how the exporting country treated US imports. The President claimed that the EU placed a 40% tariff on US goods – so the US would be placing a 20% tariff on EU imports into the US. China would face a new 34% tariff – half the claimed tariff that exists on US imports.

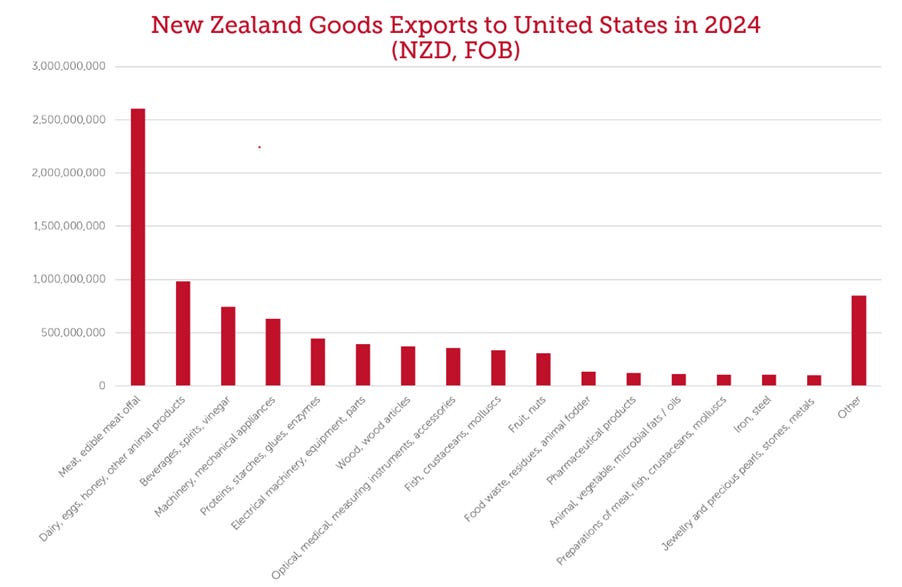

For New Zealand, the US claimed that Aotearoa had installed a 20% tariff on US goods. According to experts in NZ, actual tariffs on US goods averaged 1.9%. It was later clarified (if by clarified you mean putting out a fairly meaningless equation) that New Zealand’s tariffs were based upon:

- NZ exported US$5.6bn worth of goods to the US

- The US trade deficit with NZ was US$1.1bn in 2024.

As a percentage, that’s 19.64% – which generates the 20 percent ‘rate’ in the US numbers. On the basis of this claimed ‘20% NZ tariff’, Trump decided to install the minimum 10% global tariff on NZ goods entering the US.

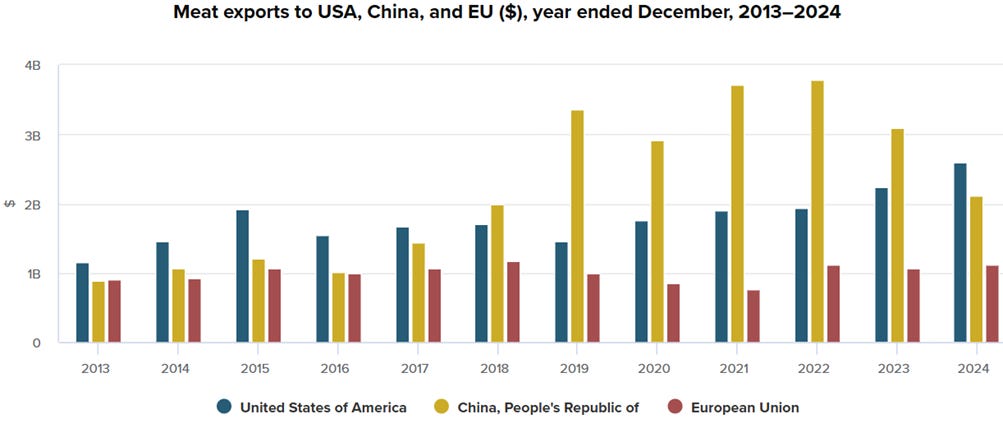

According to Bloomberg, these tariffs are new and on top of existing tariffs. New Zealand exports around NZ$9bn of goods to the US annually, meaning that costs of those goods would rise by around NZ$900m for US consumers. As an example, some cuts of beef already have a 10% tariff, meaning they will now have a 20% tariff. The US is the largest export market for our beef products across the globe, with demand for beef for hamburger patties being particularly strong.

Source: https://www.minterellison.co.nz/insights/us-reciprocal-tariff-plan-and-its-potential-impact

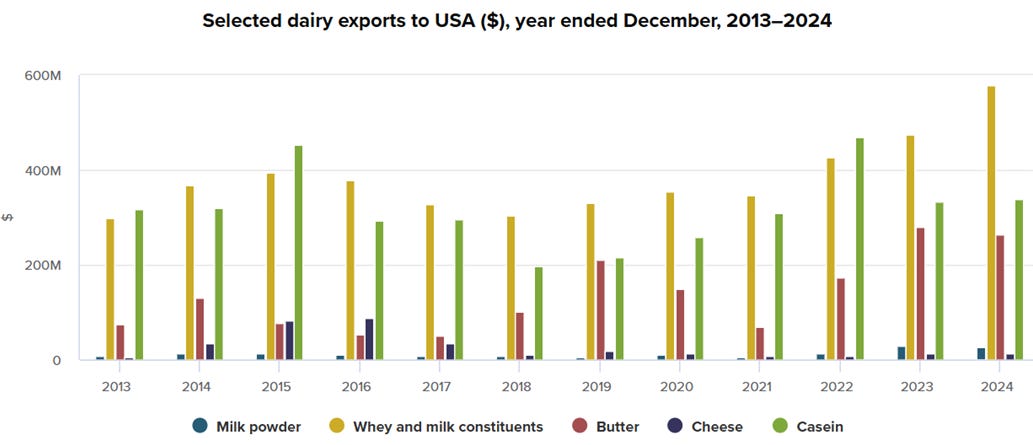

Milk powders have a tariff charged at a rate per Kg. As of right now, that is US6.8¢/kg. The 10% ‘value’ figure will likely be added on top based on the market price. The largest export to the US from our dairy industry is whey powders, which already attract an 8.5% tariff in the US. The new 10% tariff will add to that cost.

Source: Stats NZ

What does this mean for New Zealand?

Many analysts have been focussed on the fact that New Zealand is relatively unscathed from this set of tariff changes. Minister Todd McClay said that it was “the best possible result”. Certainly, a 10% tariff is much lower than being proposed to other countries such as Vietnam which is facing a 46% tariff rate.

The primary impact of these new tariffs will be economic. Demand for New Zealand goods might be reduced as the price of those goods rises in the US. This is particularly the case for agricultural, dairy, and horticultural goods as the profit margins are much smaller than for manufactured products. Small price changes in these goods (driven by tariffs) might lead to large differences in demand.

The extent to which US producers can ‘fill the gap’ created by that price increase will in part dictate the extent to which US demand falls. Secondly, the extent to which NZ goods are ‘premium’ products will be important. If NZ goods can distinguish themselves (on quality, trust, climate) then demand will be less likely to be impacted by this change.

Wine here is a good example. If the price of vintage French Champagne rises by 10% - it’s very unlikely to change the demand. Customers were expecting a high price to begin with. But should you be selling generic ‘white wine’ it’s a different story. Customers may be much more price-sensitive, and willing to change their purchase. Many New Zealand goods fall into that latter camp.

How other governments react to these new tariffs will also dictate the impact on New Zealand. China has already announced new tariffs on US imports. Many countries – particularly European countries - have responded to the tariffs by announcing that they intend to negotiate with the US before responding. If they respond with tariffs in kind, then this will slow global growth further – reducing demand for New Zealand goods and service exports.

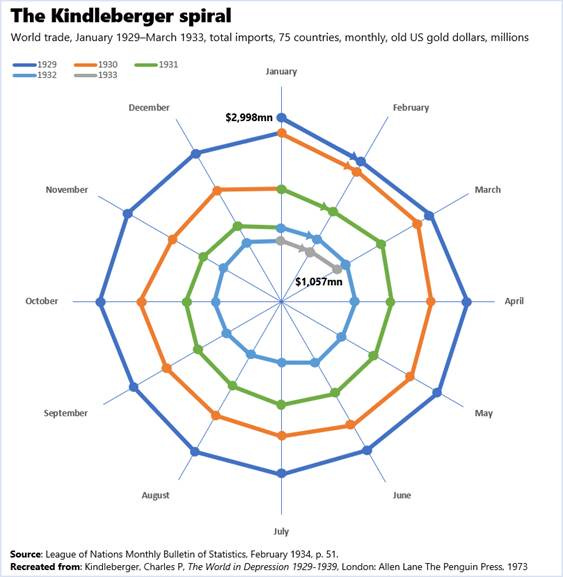

The effect of tariffs was best described by the Economic Historian Charles Kindleberger in his analysis of growing tariffs between countries between 1929 and 1933. As tariffs grew, the amount of trade spiralled down further and further. Each round of tariffs caused trade to slow further.

Diagram 1 – The Kindleberger Spiral

Source: https://tradebetablog.wordpress.com/2025/02/04/trump-tariff-kindelberger-spiral/

This is particularly the case for New Zealand markets for exports in Southeast Asia. Countries there have been hit particularly hard by US tariffs. This will very likely slow the growth and development of their economies, and with it demand for New Zealand products such as seafood and dairy produce.

Some countries will also be looking for new markets for their goods which previously may have been heading to the USA. Countries may look to ‘dump’ their goods (i.e. sell below cost price, or the price they would charge on those goods domestically) on markets such as New Zealand in order to open new trade routes. That would further negatively affect domestic economic activity by damaging domestic producers.

For New Zealand, only time will tell how negatively these tariffs will impact the economy and employment. There may even be a very short-run increase in demand for New Zealand goods as markets react.

But as a starting point, the total value of tariffs are worth around 0.2% of New Zealand’s annual GDP. If all of that value was lost, that works out at around 1,400 jobs being lost (or not created) based on data from Treasury and Stats NZ.

What Should New Zealand Do?

The Prime Minister said that “Tariffs are not the way to go” in response to Trump’s decision. He also said that New Zealand would not be launching tit-for-tat tariffs on US produce. You can mark the calendar, but I believe Mr. Luxon is right on that. Just because the US has made a mistake, it doesn’t mean that New Zealand should too.

But reacting to these tariffs is not the same thing as responding. We should respond – but respond thoughtfully. Part of the reason why these tariffs are likely to hurt our economy is because we have allowed them to hurt us. We have become dependent for our export earnings on a few narrow sectors of the economy.

In 2023, Dairy represented 30% ($21.2bn) of our exports. Between 1989 and 2023 wood exports (logs, wood, and wood articles) increased 10-fold from $0.5bn to $5bn. We now export more sausage casings ($133m in 2023) than we do carpet ($77m) – which was once one of our staple exports. Kiwifruit exports alone ($2.8bn) are nearly the same value as our exports of all machinery, mechanical appliances, electrical machinery and equipment combined.

Chart 1: Exports by Broad Category – 1985-2024

Source: Stats NZ

In short, we have become too dependent on too few exports. That makes tariffs in the US or anywhere else painful. We have built our prosperity on very narrow supports, rather than using our prosperity to build a more distributed economy. That makes us vulnerable in ways that economies that have a broader range of exports (say Australia) aren’t.

What this demonstrates is our lack of an approach over a long time to industrial policy. Rather than growing new sectors of the economy, or encouraging product diversification, we have deepened our exposure to a few product markets. It’s like going to the casino and putting everything on red. Over and over again. It works until it doesn’t.

This isn’t a call for a return to some kind of ‘Think Big 2.0’. But we should think about being happy to have so much of our economy being reliant upon milk or tourism. There are areas where we can win quickly – and moving very quickly to a fossil fuel-free transport fleet for example would be an obvious early win. It should also mean not decimating government funding for science.

Sometimes ahead of a major problem, we get a warning. We should consider Trump’s tariffs a warning. We need to take industrial policy seriously. We haven’t to date. We need to build a stronger, and more diverse economy. We can’t assume that it will turn up if we leave the economy alone – a view that the Going for Growth strategy believes when it says “Government’s role is to create the conditions”.

The Government has decided that in a more uncertain world, we need to invest more in defence. It should heed the same warning on tariffs. We need to invest more in economic development – that means more investment in infrastructure, not less as we have right now. It means making training more accessible – not less with fee increases and halving apprenticeship support. It means working on developing a long-term plan for the economy – not just the next tax cut. We can’t wait.

Wise words. Sadly I can't see this current government heeding any sort of warning and investing in anything 😟

Thanks for this cogent article Craig.

I was just wondering do you think that most Kiwis are somewhat complacent about the consequences of these tariffs on our country's economy, because we got through the GFC of the early 2010s ok-ish(perceived to get through it ok)?

People seem to think that our country is not that influenced by the global economy. This is evident in the belief(some kiwis have) that the high inflation we saw in this country, for the last 4-5 years was solely because of supposed government excess spending.

Would you agree with that?