When should you use a PPP? – A bluffer's guide

Blame Val – she asked “Craig could we please have a column on how PPPs work?”

PPPs (Public Private Partnerships) have been in the news quite a bit recently. The International Investor Summit was held this week, and promises were made about a new prison, a new road, and the Minister of Finance promised “we want to do more”. But why would a country want to do PPPs and when do they make sense? This is an incredibly brief guide.

For those of you wishing to go further can I recommend that you start here for what is happening in NZ. Can I recommend you also read here for the World Bank, here for the New Zealand Treasury, and here for the IMF. I warn you - it’s a massive rabbit hole.

What is a PPP?

The PPP literature is huge. But one thing is clear – there is no universal definition of a PPP. The Auditor General in New Zealand says “PPPs are a type of partnering arrangement between the public and private sectors”. The NSW Treasury says they are “a long-term arrangement between the public and private sector for the development, delivery, operations, maintenance, and financing of service enabling public infrastructure”. The broadness of these definitions shows you that they are essentially whatever you want them to be.

PPPs aren’t new things – we have just labelled them as new. Governments have been using private actors to do things for a very long time. Arguably the East India Company, founded in back in 1600 was a kind of PPP. But in their modern incarnation, they are a form of agreement where the private sector and the public sector negotiate the purchase of an asset, or in the case of social impact bond, an outcome. The UK is probably the first place in which they were systematically adopted. They were turbocharged as a policy idea under the Blair government with the creation of Partnerships UK.

Most PPPs involve the use of private money, expertise, and management in the building of an asset for the public sector. Older versions of PPPs were built around the idea of three companies:

Topco: The special purpose vehicle or entity responsible for the management of the contract and negotiations around any changes

Finco: The company responsible for financing the project. It can bring private equity or sell bonds to finance a project

Delco or Opco: The company responsible for delivering or operating a project.

The government had a legal relationship with the Topco. The Topco was responsible for making sure everything was delivered with the other two parts. Newer versions of PPPs brought these different parts into one company – so the TopCo and the Delco might be the same.

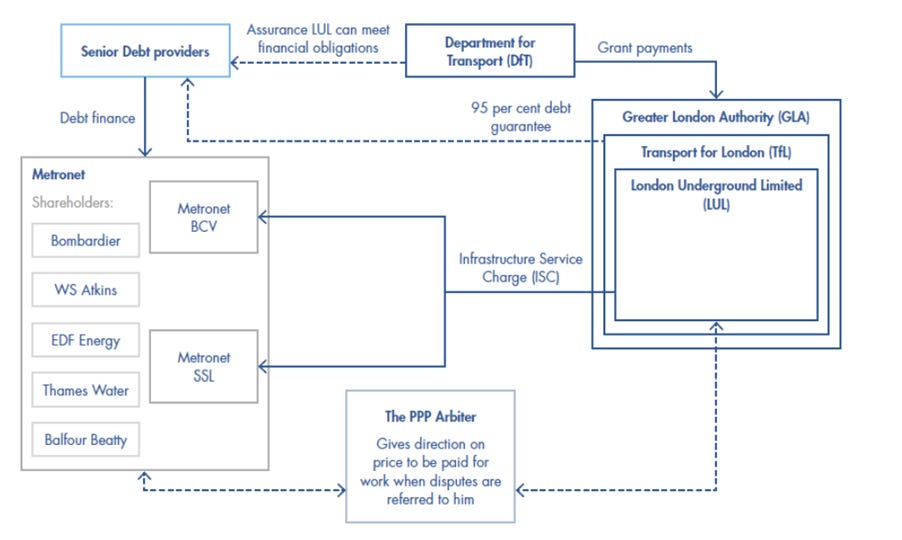

Extremely complicated rules were used to justify who did what, why, and when. The London Underground Line PPP fell apart and “certainly cost UK taxpayers not less than about £2.5 billion and possibly far, far more, possibly in the region of £20-25 billion”. The diagram below shows a simplified version of the responsibilities in that project

Diagram 1: Responsibilities in London Underground Lines PPP

So in essence – like much else in government, PPPs are usually little more than a very complicated contract. A party agrees to do a thing for a price. The counterparty (i.e. the Government) agrees to pay. Stuff hopefully gets delivered. That’s normally where the complications start.

The different types of PPP vary widely, and the responsibilities consequently vary widely. Some examples are given below:

Build – Own – Operate – Transfer (BOOT)

The private sector builds and owns a facility for the duration of a contract, with the goal of recovering costs and profit during the ‘operate’ phase. At the end of the contract the facility is handed back to the government. Often used for school and hospital contracts.

Build – Own – Operate (BOO)

This is a similar structure to BOOT, but the facility is not transferred to the public sector. Often used where the asset may be end of life by contract end.

Design – Build – Finance

The private sector constructs an asset and finances the capital cost during the construction period only. The Public Sector pays a known price but construction risk is held by the private sector or shared.

Design – Build – Finance – Operate (DBFO)

Design – Build – Finance- Maintain (DBFM)

Design – Build – Finance – Maintain – Operate (DBMFO)

Similar to BOOT, DBFO (and variations) are used in the UK, but have been used here in NZ. The private sector designs, builds, finances, operates an asset, then leases it back to the government, typically over a 25 – 30 years. The government can (if it chooses) sign an ‘option to purchase’ contract for a price at the end of the contract period

Design – Construct – Maintain – Finance (DCMF)

Design, Construct, Maintain and Finance is very similar to DBFM. The private provider creates the asset based on specifications from the government body and leases it back to them. Operations are the responsibility of the public sector. Used for prison projects.

O & M (Operation & Maintenance)

In an O&M contract, a private operator operates and maintains the asset for the public partner, usually to an agreed level with specified obligations. Service Level Agreements control payments and maintenance.

Why might Governments want to do a PPP?

Over the past forty years (if not longer) governments have been told that they aren’t very good at doing stuff. As President Reagan said “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I'm from the Government, and I'm here to help”. Since the creation of New Public Management, optimised by Gaebler and Osbourne’s view that the role of the state was to “steer and not row”, governments have been trying to do less and bring in others to do more.

Privatisation, outsourcing, contracting. PPPs are just a part of that drift away in some countries from the direct provision of goods and services and towards a contracting model. In these countries there are generally three reasons given why governments believe that PPPs might be advantageous:

Risk Transfer – Government projects, especially building projects, run over budget or timetable. PPPs seek to dispense with this risk by making it someone else’s problem (i.e. the contract holder). Governments therefore have greater certainty of cost and timetable.

Private Sector Finance – Other people’s money is always better than yours. If private cash is being put up, that means that you can use your money elsewhere. PPPs might then stretch your budgets further.

Innovation – The private sector may have a way of doing something (a technique or method) that is more efficient than the government has. That means the productivity of each dollar of investment improves. It might also mean that you get a better product than you would otherwise have got for the money.

Huge volumes of literature and analysis have been written about all three of these proposed benefits. In New Zealand, the government is focused on the first and last of these benefits, saying that “The purpose of PPPs is not to provide a financing tool – they are a project delivery model which utilises private capital for the incentives this provides”.

Overseas Governments have sometimes used PPPs as a means of hiding costs from the public – this is called ‘the fiscal illusion’. PPPs swap capital costs (which are usually debt-financed) for operational costs (which are financed out of day-to-day funding). In the past, that meant that you could hide the costs (i.e. no increase in debt) but you got the asset today. Tomorrow then pays for it. This ‘off-balance sheet’ treatment doesn’t happen in New Zealand as the Treasury considers all PPPs to be ‘on-balance sheet’.

There are specific projects where the government has absolutely no experience or practice in delivering a project. Tunnelling is an example here. It’s incredibly capital-intensive often using very specialised kit. It requires expertise that may not be readily available. You could do it yourself, and bear lots of risk, or you could get a third-party in. As the other side knows more than you, you might get fleeced. This is where PPPs are supposed to provide value.

What are the negatives?

There are many, many, many potential downsides to using a PPP. Three are the most obvious:

Cost – Using private money is almost always more expensive than public money. A 10-year NZ Treasury bond has an annual interest rate of around 4.7%. There is no way that you could get private money for that. Corporate 10 yr bonds are going for about 8%.

Complexity – Contracts for PPPs have to cover every eventuality. Even then, they fall apart at times (Hello Transmission Gully!). The more complex something is, the longer the contract, the more expensive it gets to manage, and the more lawyers you need. That all adds huge expense to what is already an expensive process. PPPs are supposed to encourage risk transfer, but instead what you get is risk ignorance. No-one actually knows where real risk lies until you end up in court.

Control – Projects can change, as the context changes. PPPs hate change, as it is extremely expensive to renegotiate the contract. Hospital PPPs overseas had controls for things like bed occupancy rates. What happens if you need to have more or less of a service – such as in the case of a pandemic? The more control you want, the higher the cost of the PPP upfront.

Politically the biggest problem that faces decision-makers is that while ‘risk-transfer’ might be real on paper, it’s not real with the public. If a hospital or school isn’t built on time, you might be able to blame the PPP contractor. Usually, the public doesn’t care. This is especially the case if the PPP contractor has gone bust. Carillion is probably the most high-profile example of this, with PPP projects coming to a grinding halt when it went into liquidation.

Secondly, there is almost always an inherent conflict within PPPs. Developers, not unreasonably, want a profit. They will seek any legal way they can to deliver that. Governments generally speaking want outcomes – better health or education. Less crime. Building a very cheap school, that also helps to deliver a great education, is almost impossible. The incentives are all in the wrong place. At Edinburgh Hospital surgeons famously had to undertake heart surgery by headlamp after the PPP provider cut off the electricity.

Finally, the problem of control is not just about managing risk. If you have a number of PPP projects, then each one will have a performance management framework. Bonus or incentive payments may be a function of these frameworks. Each one will be bespoke to the project. Suddenly, you don’t have enough people to manage contracts, which is a very specialist skill. These are the very ‘back office’ people you might have just spent an election demonising. Practically, it gets very hard to do.

When should PPPs be delivered?

This is already my longest substack post, so I’m going to keep this brief. In my estimate, the number of times that you could realistically consider a PPP to deliver infrastructure or services is vanishingly small. A great PPP would need to:

Be cheaper than the cost of public sector borrowing

Deliver innovation or benefits that cannot be reasonably delivered by the public sector

Work towards the governments policy goals rather than towards their own financial goals

Have genuine risk transfer for project delivery – with public information about why and how risk transfer has occurred

Not further diminish the role of the state to deliver assets or services in the future

Just the first of these bullets alone is enough to stop most projects. But I would like you to think about how genuinely few government investment opportunities would meet this criteria.

That’s also the view of the Treasury in 2006 which said of PPPs:

There are other ways of obtaining private sector finance without having to enter into a PPP

Most of the advantages of private sector construction and management can also be obtained from conventional procurement methods (under which the project is financed by the government, and construction and operation are contracted out separately)

The advantages of PPPs must be weighed against the contractual complexities and rigidities they entail. These are avoided by the periodic competitive re-tendering that is possible under conventional procurement.

To Conclude

When someone is trying to tell you that they have a great deal, it just involves cubic metres of paperwork, corralling armies of lawyers, and understanding intimately diagrams that look like nuclear submarine wiring specifications you would be right to be suspicious. There might at the very edges be a good case for a PPP, but it would be very rare. Great financial cases for PPPs would be even rarer.

We should also just stop for a second and ask ourselves a more fundamental question – do we want New Zealand’s ability to run key public assets – like prisons – to be a function of a long-run contract between a private provider and the government? Do you want to rent, for however short a period, a hospital that an entire city might depend on? Do you want the maintenance decisions for your children’s school to be a function of decisions made by people you will never see, and over whom you have no democratic control?

PPP use is in decline in Canada. Parliamentary evidence from their use in the UK says “Weighted Average Cost of Capital of a PFI [a type of PPP] is double that of government gilts [borrowing]”. We don’t have a public debt crisis in New Zealand, but we do have an infrastructure crisis. We do have a crisis of capacity to deliver the actual projects needed, not a shortage of money – and certainly not a shortage of opportunities for private profit to crowd out public policy goals. PPPs won’t solve those problems.

Thanks for this great explainer Craig (even with the overwhelming number of acronyms 😂).

Of course all of this is corruption- the conveyor belt of public money to private bank-accounts- just not 'illegal' since it's done at the level of government sector / private sector rather than at the firm-to-firm level, and parliament as a whole as well as ministers are protected from the consequences of it by 'privilege'.

Government wantonly made both themselves and Councils 'not good at doing stuff' by abandoning the Public Works Dept and City Engineers Depts. These offices need to be reinstated, not necessarily as full vertically integrated services, but certainly at the project development & management level. Part of the problem is that competent engineers are expensive, even more so if deprived of the opportunity to ride the 'revolving door' on the way out of public service- which would be a necessary condition of service to guarantee loyalty to the public service ethos. This might cause conflict with CEO's over salaries.

Concerning large-scale projects.: The Judiciary has been found wanting in its favouritism to the contracting industry over government. The Transmission Gulley partnership successfully sued the government for 'extras' demanded for remediation of unstable ground in an environment where the possibility of such conditions were predictable and ought to have been insured against by the partnership or borne out of their own resources. This sends a message to future PPP partners that it's ok to tender low to get a contract then use the law to get top-ups as required.